Original Post: Nature India blog

Having achieved an H-index of 100, Rajeev Varshney* explains what the metric means in scientific publishing and why it is a milestone, especially in an agricultural scientist’s life.

H-index is an author-level metric that measures both productivity and citation impact of an author’s publications across the global scientific community. It is calculated by counting the number of publications in which an author has been cited by other authors. H-index 100 means each of the latest 100 of the author’s papers have been cited at least 100 times.

Opinions vary on these metrics and the number of citations is not the only way to measure scientific impact. But it certainly is one of the many metrics that recognise scientists’ publishing lives, and in turn, their science. Research publications are a great way to share the latest advancements in science with the global community. They also help reduce redundancy or duplication in research while directly or indirectly saving the valuable time and effort of the scientific community as also taxpayers’ money.

Generally speaking, medical science generates more research innovations that are used by different biological disciplines, including agricultural sciences. As a result, citations in medical science research are higher than agricultural science publications. When agricultural science publications have high citations, it does indicate that the research is making an impact in advancing science. The milestone of 100 h-index is a recognition of the high-quality science at ICRISAT with colleagues and partners from across the globe.

The metric that matters even more

The real battle that agricultural science should wage is against hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition. Scientists in the same discipline anywhere can learn from the latest research and take it forward to address issues of smallholder farmers while advancing the cause of scientific research for global good.

As scientists, we believe in every study we conduct irrespective of the results we get. Some of the research we conducted with a large number of global partners has an edge over the others because of massive learnings from the multidisciplinary scientists involved. For example, our genome sequencing work of 429 chickpea lines was a collaboration of 39 scientists from 21 research institutes across 45 countries. It tapped next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology to better understand the genetic architecture, centre of origin, migration route as well as genetic loci for agronomic traits in chickpea. This study1 with several brilliant minds from across the world offered much learning for me.

There is a great sense of satisfaction when the upstream research we conduct delivers results in farmers’ fields in addition to advancing the cause of science for global good. As a genomics scientist, I provide research outputs for breeding programmes that develop improved crops.

ICRISAT’s collaborative work on genomics-assisted breeding helped develop and release the first set of products in 2019. There were three high yielding, wilt resistant varieties of chickpea2, 3 and two high-oleic varieties of groundnut4. The Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research also released a high-yielding chickpea variety5. The groundnut varieties were among the 17 biofortified crops dedicated to India on World Food Day 2020.

My efforts in genomics-assisted breeding will continue with an aim to accelerate the replacement of older crop varieties to help smallholding farmers improve their income and ensure better nutrition and health for the society.

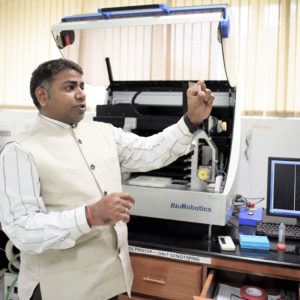

(*Rajeev Varshney is Research Program Director, Genetic Gains and Director, Center of Excellence in Genomics & Systems Biology at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), Hyderabad, India.)